When you have been impacted by a disaster of any kind you are frightened, scared, often very angry and the last thing you need is to fill out forms and answer numerous questions from strangers clamoring to HELP you. So why is it that the majority of our disaster assistance and recovery programs at all levels fail to understand that emotional issues can seldom be resolved by analytical processes?

At a hazards mitigation conference I once attended, one subject kept coming up (albeit often in side conversations): how can we do better with natural hazards preparedness and mitigation? At all levels of government and private industry, the fact that billions of dollars are being spent annually often with very little result is becoming a major concern. That the largest risk companies now estimate that the cost of hazards damage is starting to become incalculable is scaring even the wealthiest countries. The big elephant in the room was the fundamental question of whether it is even possible to understand a subject with massive emotional dynamics through analytical means.

Should this be approached in a very different way? Any victim of a disaster in which their world has imploded in 5 minutes is naturally frightened, upset, and scared. To introduce a program of any kind, no matter how well-intentioned, that does not explicitly recognize this adds additional trauma, leading to complex issues lasting for years.

Two of the presenters at the conference made a huge impact: elders from the Chitimacha Tribe of Louisiana; and Sallie Clark, a Commissioner for El Paso County, Colorado. Their messages were different, but interconnected. In sum, they both stressed the importance of knowing your community and reacting in both a human and efficient systems way, or as Sallie stated so eloquently “Yes, indeed we need to be efficient in our response to a disaster — but let’s not forget that sometimes they just need a hug.”

The Chitimacha (Sitimaxa, “people of the many waters”) are famous because when the FEMA team got to their reservation three weeks after hurricane Katrina, they had already taken care of most of the damage. Communication in the tribe took place mostly by word of mouth, with CB radio assistance. Within 24 hours after the storm had passed, all 1,100 members of the tribe had been contacted by a tribal council team and all needs, both physical and emotional, were being attended to. Rebuilding had started, and in many cases was complete. A major focus of the tribal council was on emotional support, and this ran consistently throughout everything they were doing.

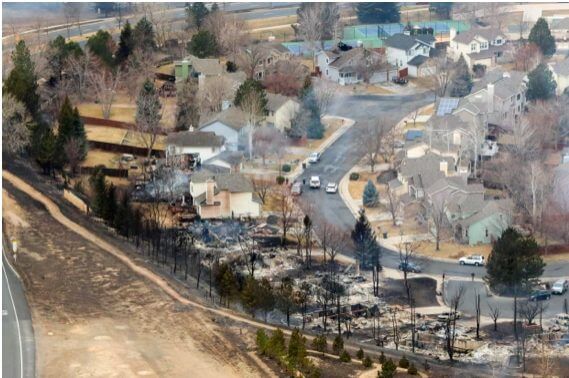

Sallie was doing something similar after the 2012 Waldo Canyon fire devastated her Colorado Springs community. That wildfire was one of the most destructive in Colorado history. It took two lives, destroyed 347 homes, forced tens of thousands to evacuate, and insurance claims topped $450M. Sallie’s response: identify everyone impacted, ensure they have a case officer attending their needs both physical and emotional, and simply make sure they have a shoulder to cry on. She personally drove to evacuation shelters and made sure this was being done and gave anyone a hug who needed it. A truly shining example of “WE CARE!”

On the second-to-last day of 2021, the Marshall fire in Superior and Louisville (Boulder County, CO) surpassed the Waldo Canyon fire in destructiveness and impact, and again brought this issue to the fore. About 1,200 people were directly affected by the fire (almost the same number as the number of Chitimacha tribal members impacted by Katrina), over 1,000 homes and buildings lost, but here we are with forms and bureaucracy pouring from the skies, bureaucrats running around in circles getting air time, and not a shoulder to cry on.

Two organizations stood out to me in this particular disaster, and it may surprise you who they are: the local government research labs and the churches. Two very different organizations that reacted very similarly. NTIA, NIST, and NOAA have a large presence in Boulder, and naturally many people who work in these Department of Commerce labs were affected. Part of a supervisor’s job in those labs is to maintain and work what they call the “telephone tree,” which is really simple and unstructured. In ANY event the supervisor must contact all of his/her direct reports and ensure they are OK and respond to ANY issues they may have. Within 24 hours of the fire’s impact they had done exactly that. Anyone affected was on full pay with no work worries. Unaffected employees offered their affected colleagues a place to stay, clothing, food, and transportation, and supervisors connected those in need with the appropriate offer. Access to medical and psychiatric support had been organized and from the community of federal friends (including contractors) hugs and shoulders to cry on were plentiful. On the other end of the organizational spectrum, the Quaker Meeting (and other congregations in all the towns around Boulder) were doing exactly the same thing, and again within 24 hours their contact task was complete and now case managers’ support and shoulders to cry on are in full swing.

It seems weird to me that many senior executives from both Google and Twitter have a major presence in the area, but cannot emulate something so simple with their so-called advanced media despite making millions from the disaster. It is also bizarre that the Office of Emergency Management is posting all its information on Facebook only, and in such a way that if you don’t have a Facebook account you cannot read their posts. Distance sends a message: “we do not care.” Blatant disorganization sends the same message. Leaving outreach in the hands of a group of politicians in masks on a stage is beyond callous and enforces the belief that nobody cares.

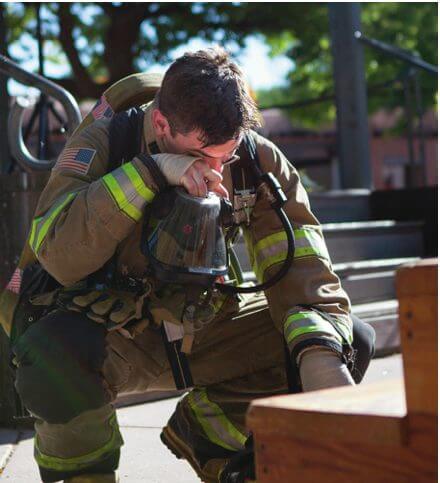

Another group on which these disasters take a huge toll is often forgotten, and that is first and second responders. First responders are, of course, the fire, emergency medical, and law enforcement crews who are on the scene first. By second responders, I mean the service crews who arrive to handle the disaster impact and start recovery and restoration.

At the conference where I met Sallie, one of the presentations was about psychological impact on teams responding to disasters, focused on FEMA employees. The impacts on these teams are well known. If the people directly impacted by the disaster do not get immediate physical and psychological support, their grief, fear, and uncertainty translates to anger — which is transferred to the first and second responders. The toll that takes on them is incalculable. PTSD becomes shared as they face a vision of hopelessness and futility day after day after day.

Many second tier responders are not well-trained and constantly drilled, as the first responders are. They are often volunteers, or “detailed” in to meet the surge in demand for warm bodies. They quickly become overwhelmed, and, as FEMA’s own data shows, within that cohort suicide, marital strife, and drug and alcohol problems soar. Not surprisingly, one of the most common laments the psychologists heard was “if only I could have gotten some emotional support right then and there.” When FEMA was asked directly how they provide emotional support to their teams, it should come as no surprise that the training was mostly analytical, and 60% of it addressed how to respond to media inquiries. The Brits call this “keeping a stiff upper lip,” but that isn’t helpful if you are thinking of killing yourself.

Swiss Re, a major risk reinsurance company based in Zurich and Frankfurt, maintains the proprietary CatNet® (CatastropheNetwork) tool that mines worldwide satellite imagery, country-specific insurance information, and historic loss event data to diagnose, classify, and manage risk. Boulder County Colorado is in the high desert on the eastern slopes of the Rockies, where droughts and water shortages are natural. This area is classed as being at high risk for fire followed by flood, and on Thursday December 30, 2021, when the winds gusted to over 100 mph the chances of fire raised the risk category to catastrophic. But what could be seen thousands of miles away was apparently invisible locally, even with the presence of a NOAA National Weather Service lab right in Boulder.

This leads the victims of the disaster to conclude not only that those charged with prevention and oversight are badly failing, but they have no interest in finding real solutions. This will drive the anger quotient through the roof, and sadly the people who will bear the brunt of this anger are the first and second responders. This in turn sets up the sort of friction that in one case led to the arrest of a distraught homeowner for trespassing and menacing. None of the people in control (sic) seem to understand the extent of the trauma involved. They remain distant, sending out massive quantities of paper and media. Having placed the victims in large temporary shelters and left them to fend for themselves, passing the responsibility on to those who are already overwhelmed, “management” congratulates itself on having done its job.

Yet another issue that tends to be swept under the rug is the impact of emotional stress on those surrounding the disaster area. Those whose homes were not directly impacted by the initial fire damage but who had been evacuated are now returning to homes that have been disconnected from all utilities and contaminated by smoke. Every day as they try to rebuild their lives, different emotional storms enter their lives. There’s survivor’s guilt, as often right outside their window and certainly every time they leave their homes, they see the visible evidence of devastation. The feeling of “oh, my God, we are so lucky” alternates with feelings of helplessness when they witness instances of devastation barely feet away from structures that appear perfectly untouched. The inability to “make sense of” the contrasts can be overwhelming. On children, these effects are devastating. The sooner some semblance of normality is returned to them, the better, as this form of associated PTSD can have a long life and create massive pressures on family life. The message from the get-go needs to be “we care and will take care of you,” and if this fails, so do all the accompanying efforts.

So we see a culture with 1,500 years of history that has survived more disasters than the U.S. has ever experienced; Sallie Clark, a very smart County Commissioner; some adroit federal labs; and some caring religious congregations all using the same solution. These people all demonstrate a shining example of doing it right. If you think the solution is to clone Sallie and the Chitimacha way, I think you are right on.

Pete is a frequent speaker, lecturer and writer on best practices and the pursuit of excellence and how they work in the real world. He has been a Board Member of the Natural Hazard Mitigation Association, a Member of the American Society for Quality and the American Society of Civil Engineers, and an Advisor Member Guru of Engineers Without Borders.

IMHO Zoom is a lousy way to give hugs

Pete, a firefighter friend shared your article with me. Waldo Canyon Fire seems like so long ago and yet strangely just like yesterday. Thank you for bringing the support of mental well being as a topic of importance, especially in light of the recent events in Boulder County following the Marshall Fire.