To all my friends, city staff, colleagues on the energy municipalization effort at the City Boulder It might be a good time to lay out some issues from my point of view or IMHO regarding steps forward either with or without Xcel or any partner. My focus is that of a risk assessment engineer skilled in operational efficiency of large infrastructure including power utility operations. It is in that role that I have served on several of the muni committees. My passion is excellence and how it can be achieved—period, end statement.

I tend not to get involved in esoteric discussion about whether this or that target is “good” or “bad” or (worse) “evil,” but to look at the fundamental functioning of what is working well or not in a systems operation. My goal is to make this visible to all sides, and there are usually several. “Benefit to mankind” or “Dinosaur extinction comparisons” is not something that even appears on our radar. Unless basic operations are understood, your admirable future goals tend to be of little value as the system collapses.

All utilities worldwide, whether massive or small, base their operational plan on the fundamentals of supply-demand balance, and any power source that does not function within this parameter is unwieldy and expensive. Demand comes in peaks and valleys, and supply must be tailored to this. Generation – Transmission – Distribution are three parts of the balancing act and all need a common focus as an out of balance utility will fail. Until we get terawatts of storage—whether pumped or battery or another kind—the operating principles to balance supply and demand remain unchanged, as they are driven by the basic grid design across the US and every reliable energy producing country in the world.

Personally, I think the focus on cheap energy at all costs as the swing engine of an economy is wrong because every base fuel ever used (or that will be used in the future) has economic highs and lows. Sadly, chasing cheap energy seems to be the law of the land, and the end result (both economic and environmental) will be with us for a long time. The premise that it is possible for an energy system to achieve excellence in environmental effects and deliver at the cheapest price (equal or cheaper than today) is a total oxymoron. It’s a “formula” that does not work in any industry, let alone power. The current supplier of your energy lost its contract to the city because, bluntly, it was perceived to be using a mediocre system and labeling it excellent—note the emphasis on “perceived,” or question by whom among the chattering classes of Boulder!

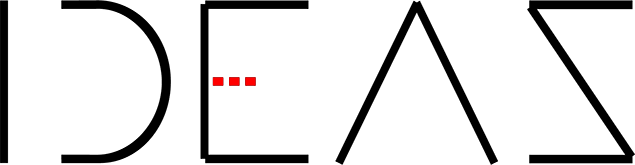

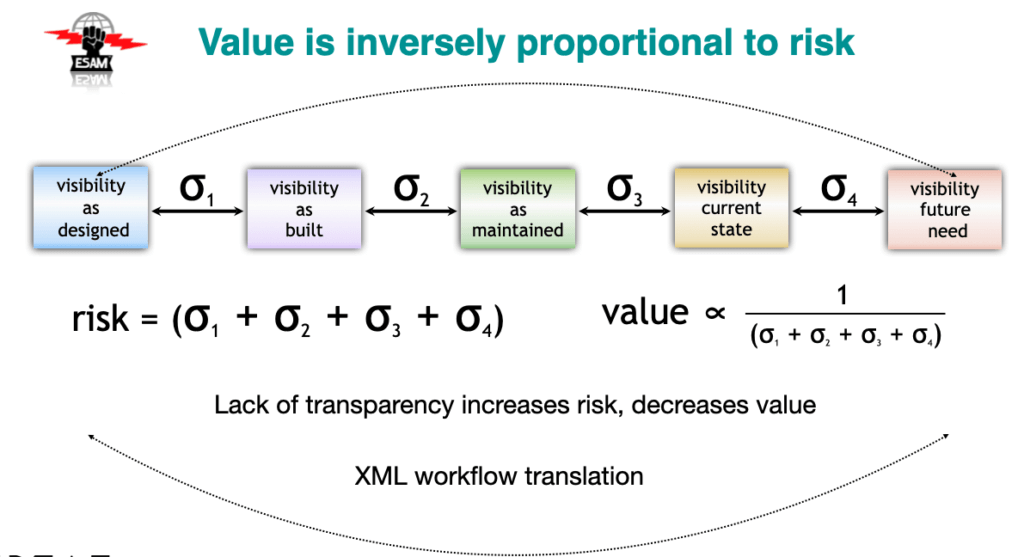

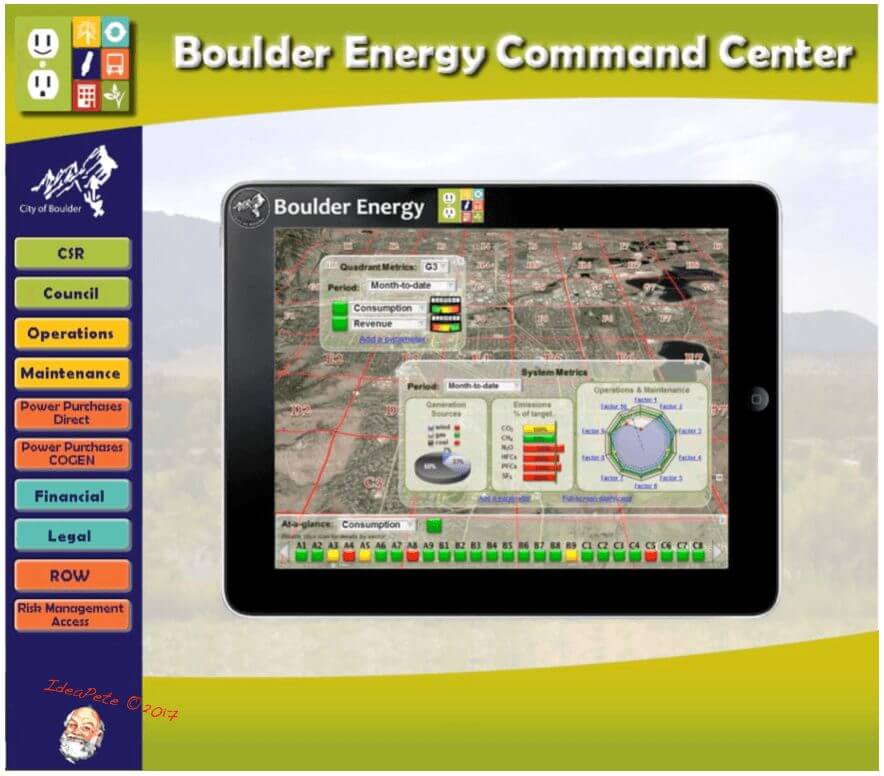

In risk exercises, we use simple metrics to examine any system’s performance. First visualize the system in real time, then we organize it, and finally optimize its operation.

Knowledge of a system’s real-time operational efficiency is important because if a system has components that are not designed / built / maintained (which dictates future performance capability) in such a way that actual and future system state is verifiable (by every stakeholder), then the system will be expensive to run and have high risk, high total cost of ownership, and high failure rates, the negative cost of which is largely borne by the businesses and homes who depend on it.

The condition of the current (pun) system determines its full asset value, currently (pun 2) and going forward.

So how to find out?

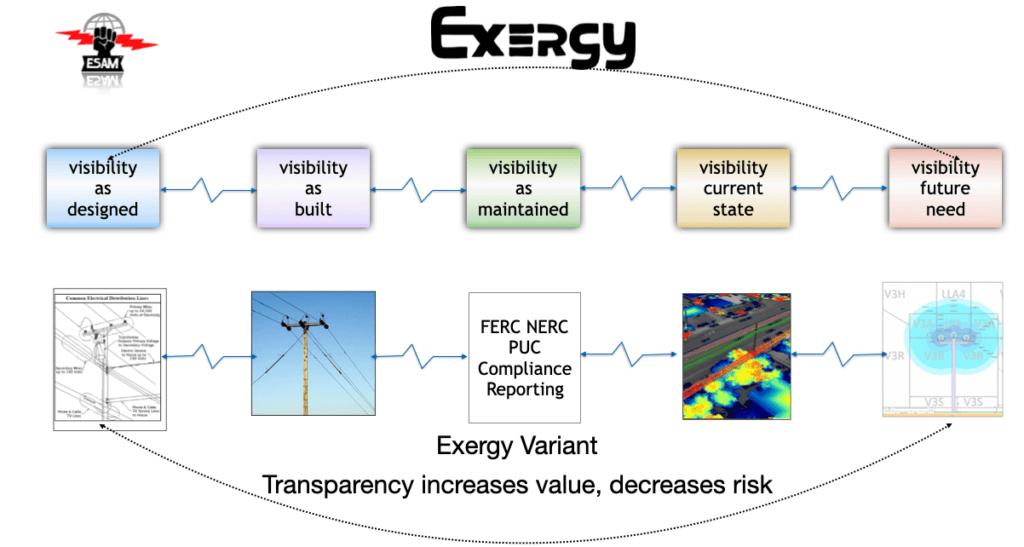

Every single major electrical component in the city is visible one way or another, with poles and wires, substations, and transformers being the most accessible. A simple airborne LIDAR examination can be carried out, a survey that for the full city and county would take 5 days including data transmission to an evaluation source at a cost of about $600K. Every component whether pole, wires, vegetation, transformer, or meter would then be documented and available for assessment in a master model. The actual captured image can be compared to specs to determine if it really was designed, built, maintained to the accepted specifications listed. If not, then the operation’s value and total cost of present and future operation, including the cost of risk, is easily determined, as well as. The additional cost for this kind of in depth analysis of the gathered data is about 50% of the cost to collect the data, or about $300K.

You cannot determine if a system is providing you with a satisfactory service level until this is done, let alone increase the service levels to higher standards of excellence, which the grid of the future will entail. Systems that have large variance among designed, built, maintained, actual, and future operational state always fail more than ones that do not. It’s simple systems engineering: crap winneth out, period.

You also have to prove to the industry’s regulators and governing forces that you are acting in compliance with their directives and this is, many times, not an easy task.

So who is correct on the system’s condition, the City or Xcel or the PUC or the consultant armada, and why hasn’t the above audit been carried out? Really good question, and maybe either side can explain.

A major part of the focus of the muni exercise has been on sustainable generation goals and the effects of operations on global warming. These are admirable goals—but they have drowned out the basic engineering analysis, and without those basics all well-intentioned dreams will come to naught. Systems collapse because a poorly designed, built, and maintained actual and future operational state causes power failure and worse (think PG&E), no matter what the base fuel source. Yet sadly one most important component is missing: how to track these wonderful directives. And why, when a tracking system is suggested and demonstrated (see below), is the suggestion ignored? That does not speak well for verifiability of the city’s goals and actions.

I have watched several crusades in the city, many with very passionate adherents, but one thing is very common—shift of focus as a new crisis comes along, with the goal of short time to resolution. The power and energy supply industry has to focus on clear definition and support of long term goals, 50-100 years or more, and support these with a really good vision of what needs to be done at the basic level for a complete system, not just one part. This also applies to the city’s infrastructure, as it is naive to think that a municipal energy system will run perfectly when roads, pipes, and other infrastructure services are not apparently run well. Disagree? Show me similar due diligence.

City infrastructure, as a whole, is undervalued by about 70% or more—yes, that’s what I said 70%—and so the maintenance and upgrade numbers are off by a similar %. Brilliant tax base move, but not wise for the city’s future, and all Boulder reserves are about $275M, a drop in the bucket compared to what is needed for an energy system of the future. So why should we think the muni will be any different?

The city operates under a very strong imperative to contain liability (driven by its legal department) as opposed to guaranteeing high service quality and driving out poor performance. This is not the way any utility of the future needs to operate, as it’s at cross purposes with its responsibility to its citizens. The poor performance of Xcel (whether real or imagined) was in fact a major driver in the city’s “maybe we will maybe we won’t” refusal to sign its new 20 year contract and probable future one.

It seems currently that the city (people not politicians) is losing its appetite not only for the muni but to hold Xcel’s feet to the fire on any new service level agreement contract (or know how to as the SR committee found out). The situation is made even more difficult by the lack of good data, and any dispute will collapse into a “he said, she said” which helps no one.

David Eaves is an excellent poker player and he knew well that the city’s capital and voter appetite would wane at around $8-10M, especially when that is targeted to massive amounts of paper and nothing else, and that a true system retrofit and re-design evaluation implementation test, to achieve high quality, including legal costs, would go to near $15-20M+, which is peanuts in a $400-600M system. If you don’t have the bucks, you cannot sit at the table. If you are nervous, don’t play and never, ever play poker by committee.

The municipalization funding stakes start to evaporate at the end of the year 2017 and chances of renewal are real slim (yes, slim, even after getting a wafer thin margin of advancement by giving free pizza and coke to students), due in no small part to the barrage of criticism from scribes who probably could not tell you which end of a generator to connect to the grid, no matter if their life depended on it, but who are adamant that instant understanding of the city’s energy future and survival strategies is well within their purview and scope of knowledge.

Despite assurances from many directions and the kumbaya noises being made, all the news I’m hearing in the industry, from other energy companies, analysts, and industry experts, is that the Boulder muni effort is dead and buried, no matter how many meetings occur or how many zombi revivals happen .

The blunt truth is that Xcel, and their (kudo plug to linemen everywhere) great team working 365/7/ 24 in all weathers have the experience and know how to run an energy system and the City of Boulder does not.

I have thoroughly enjoyed working with the eclectic group of passionate individuals on all the committees with the utility team across the aisle, but unfortunately in the energy excellence business, nearly doesn’t do it. We came close, damn close, but next time let’s focus on the basics and foundations before we dream of bigger things.

Be well, live long, and prosper.

Pete : ) ; )